When the Beckham-wagon rolls through, should brands follow?

What reactive content reveals about long term brand strategy & the temptation to remain relevant in crowded social media feeds.

January is always a bit brutal. One minute you’re losing track of the days between endless chocolate and reruns of The Holiday; the next you’re back at your desk, staring at the news cycle and wondering how the world managed to get louder while you were eating mince pies.

This year, the backdrop has felt especially heavy. Global politics, protests, endless wars, economic anxiety — it’s relentless. So when a celebrity family feud erupted across Instagram a couple of weeks ago, it almost felt… convenient. A distraction. Something lighter to talk about on the tube, in the office kitchen, or in the WhatsApp group that hasn’t mentioned interest rates in at least five days.

Brooklyn Peltz Beckham publishing a six-page Instagram story laying out his feelings about his family to 17 million followers did exactly what these moments always do. It broke containment. Memes followed. Hot takes multiplied. Hashtags climbed. And, almost inevitably, brands joined in.

Which is the question I keep coming back to:

just because something is everywhere, does that mean brands should be there too?

When culture outruns judgement

If your feed looked anything like mine, the response was immediate and expansive. Creators riffed on it. Even ChatGPT took a side. News outlets framed it as cultural theatre. Even other celebrities waded in like Lily Allen — sometimes with a wink, sometimes with a product quietly attached.

What’s easy to miss in all the memes is that this wasn’t just celebrity drama — it quietly surfaced questions about identity, control and who actually owns a name once it becomes a brand. If that sounds abstract, Tamzin Burch’s Intellectual Gossip piece on Brand Beckham™ is worth reading; it turns a viral celebrity moment into a surprisingly sharp lesson in trademarks, power and consent.

And once a moment carries that kind of emotional and structural weight, it changes what “reacting” actually means for brands. This is where reactive content stops being a quick cultural nod and starts becoming a decision about proximity, judgement and responsibility.

Reactive content isn’t new. It’s been a part of social strategy for years. What has changed is how close brands are now willing to stand to real people, real families and unresolved situations and how quickly that distance collapses once performance metrics start lighting up.

I’ve had countless conversations about this over the past few days. Some people firmly in favour. Others deeply uncomfortable. Enough tension there that it felt worth slowing down and writing it out.

Yorkshire Tea: wit, well deployed — and slightly stretched

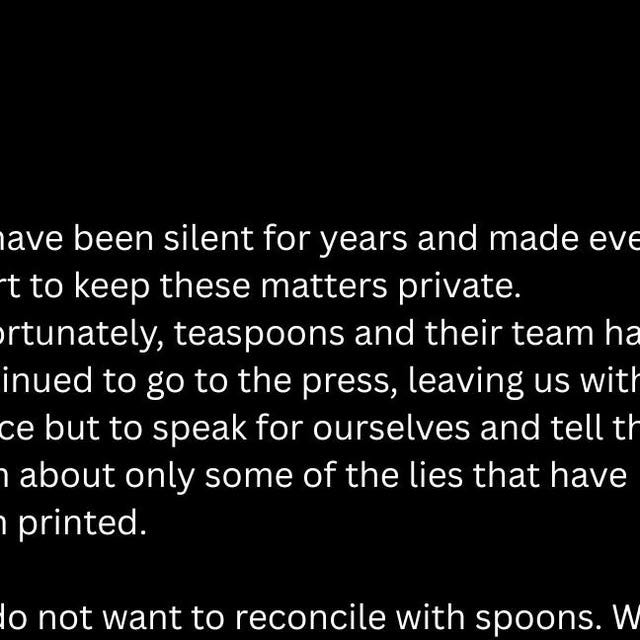

Yorkshire Tea, a tea brand, were quick to respond, publishing a three-slide Instagram post that mirrored the tone and structure of Brooklyn’s statement, but replaced the family conflict with an absurd metaphor about spoons ruining their relationship with tea.

It was unmistakably Yorkshire Tea. Dry, self-aware, and written with confidence. Strategically, it made sense: this wasn’t a sudden tone pivot, but an extension of a brand that has spent years building equity in British understatement and cultural parody.

It also worked, at least in the short term. Engagement was strong and praise followed. But so did discomfort. Some people loved it. Others felt uneasy about using the emotional structure of a real family conflict as a comedic device.

That tension is the point. Just because something is on-brand doesn’t mean it’s on-mission. Beyond reminding us that Yorkshire Tea is witty, the post didn’t deepen what the brand stands for. It borrowed emotional gravity for contrast and that’s where the wobble crept in.

As Mark Ritson would likely ask: you’ve won the moment, but what memory are you actually building?

Deliveroo: cultural proximity without a point of view

Deliveroo, a food delivery app, took a different route. The post — shared on Instagram and TikTok — featured a Brooklyn-Beckham-ified version of Lily Allen’s album cover (originally designed by artist Nieves González), reworked so Brooklyn appeared in a Deliveroo jacket, captioned: “pov: brooklyn delivering the tea last night.”

It performed well. Scroll the comments and you’ll see the applause — “genius”, “give the social team a raise”, industry approval all round. On the surface, it looks like neat reactive content: timely, restrained, careful not to say too much.

But creatively, this sits in a different territory. This isn’t satire or abstraction. It’s visual insertion. Deliveroo didn’t comment on the drama; it placed itself inside it.

That distinction matters. Using someone’s likeness, even via AI, doesn’t make the association disappear. If a person is recognisable, audiences still read it as them. From an IP and governance perspective, this nudges the work into questions of personality rights and implied endorsement. AI may soften the visual edges, but it doesn’t remove the commercial connection. That doesn’t make the execution automatically wrong, check that with your legal department or friendly lawyer, but it does mean it isn’t neutral.

More revealing is what this says about brand priorities. Deliveroo’s mission is rooted in convenience, community and making everyday moments easier. Historically, it’s a brand built on service, reliability and operational excellence rather than cultural commentary.

This post doesn’t clearly ladder back to that. There’s no product insight or service truth being reinforced; just recognition and cultural heat. A moment borrowed, briefly worn, then moved on from.

That isn’t inherently a mistake. Some brands choose relevance over consistency. But it does signal short-term orientation. If you measure success solely by engagement and industry praise, this worked. But if you look at the brand metrics that actually compound over time — fame, the associations people hold, whether they’d choose you over someone else, whether they come back, whether they’d recommend you — the picture becomes far less clear. Visibility is easy to buy or borrow. Preference, trust and emotional loyalty take much longer to earn, and much longer to repair if diluted.

How other brands played the moment

It’s also worth saying that Deliveroo wasn’t alone. Several brands climbed onto the Beckham-wagon, each revealing something slightly different about their instincts.

On the Beach, a package holiday provider, moved fastest and loudest, turning the moment into a tactical product hook with its “Beckham clause” — agile and engineered for headlines rather than heritage. It made sense for a brand selling holidays, where immediacy and conversion are part of the deal.

Reformation, by contrast, chose a very different vehicle. They used email, not social, and let copy do the work. The subject line — “Dancing Inappropriately” — was a quiet, knowing nod delivered in a tone of voice so distinctive it didn’t need explanation, visuals, or amplification. That kind of restraint only works when a brand has spent years refining how it speaks.

Mercedes-Benz sat closer to Deliveroo’s territory, using AI-rendered visuals and recognisable Beckham cues to signal cultural fluency, but in doing so leaned more on association than meaning. Across all of them, the pattern is clear: the closer brands move to likeness, realism and visual insertion, the more they risk overreaching. The lighter, more abstract the touch — where format is borrowed but emotional weight is left untouched — the more the brand, rather than the moment, is what lingers.

Coldplay vs Beckham: why brands behaved differently

The Coldplay concert moment last summer looked similar on the surface: real people, a viral clip, the internet piling in. But some brands treated it very differently and rightly so.

Coldplay wasn’t celebrity culture. It was private individuals accidentally pulled into public spectacle. No pre-existing “brand of fame”, no media training, no expectation that personal moments might become content. The power imbalance was obvious. Real families, real jobs, real consequences unfolding in real time. That’s why the online chatter felt more cautious, and why many brands stayed silent.

Those that did engage kept their distance, like Netflix, IKEA and Paramount did engage. They avoided individuals and judgement, staying in metaphor, mascot or product-led territory. The further brands stayed from real people and unresolved harm, the more the work held up.

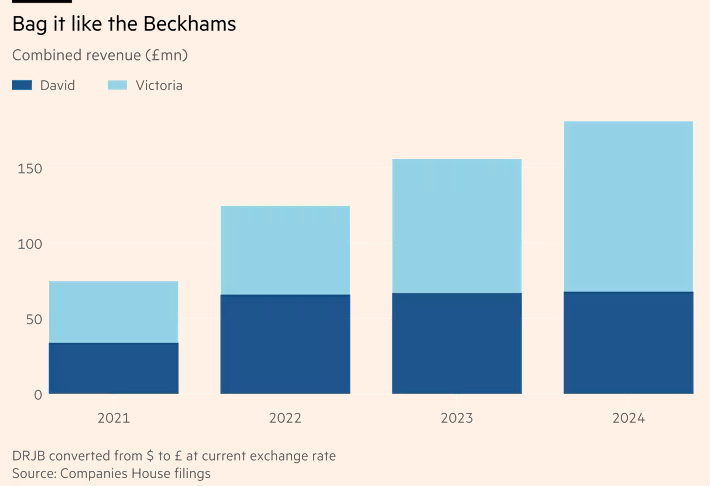

The Beckham situation sits in a different cultural lane. The Beckhams aren’t just a family; they’re a celebrity brand, carefully constructed and monetised over decades, with combined revenues now comfortably in the hundreds of millions and an estimated brand value nudging into the billion-pound range — a scale that gives their empire far more shock absorption than most. Their lives already exist within the cultural economy. That doesn’t make family conflict fair game, but for some brands, it does lower the perceived risk of proximity.

Lower risk, though, doesn’t equal better strategy. The question isn’t only “is this allowed?” but “what does this build?”. ColdplayGate showed that virality alone doesn’t create brand equity when the brand has no natural role. The Beckham moment shows something similar: even with higher cultural licence, the upside is often short-term salience rather than lasting meaning.

Renting relevance is easy. Owning meaning is harder.

Heritage brands, challenger brands, and the real decision

This is where the debate often gets oversimplified.

For challenger brands, moments like these can genuinely matter. Attention isn’t a nice-to-have; it can be oxygen. Opportunism can be rational when visibility is the goal.

Heritage brands don’t have that same excuse. If your brand is meant to last decades rather than quarters, every cultural shortcut compounds. The question shifts from “will this perform?” to “what behaviour are we normalising?” Restraint becomes a strategic asset, not a weakness.

Which brings me to the real question. If this were my brand or my boss/manager/client asked me, “Should we do one?” my answer wouldn’t be yes or no. It would be: who are we, what is our strategy; what are our values?

Michael Corcoran’s point about moral compasses shifting with proximity captures this perfectly. When everyone’s feed is shouting the same thing, judgement softens. Decisions start to feel right because they’re culturally fluent, not because they’re strategically sound. That’s usually the warning sign.

If the main upside is short-term reach, applause in the comments, and a Slack thread celebrating the numbers, I’d push back. Not only because it’s immoral — but because it’s lazy strategy dressed up as bravery.

Should we post?

A practical framework for the next time “should we post?” lands in your inbox:

1. Brand first, trend second

Does this moment reinforce what the brand is already known for, or are we stretching tone to chase relevance?

2. Distance from harm

Are real people, real pain, or unresolved personal situations at the centre of this trend? If yes, tread carefully — humour doesn’t neutralise context.

3. Role clarity

Are we the punchline, the commentator, or the opportunist? If you can’t explain our role in one sentence, we probably shouldn’t play.

4. Memory test

In six months, what will people remember — the brand, or just that we “posted on it”?

5. Rights & governance check

Are we using names, likenesses, formats or implications that create legal, IP or ethical grey areas? If you need to squint to justify it, pause.

6. Incentive honesty

Is this being driven by brand strategy, or by the dopamine hit of likes, shares and internal praise?

7. Walk-away confidence

If we don’t post this, do we still feel strategically sound? If silence feels like failure, that’s a red flag.

This isn’t about killing speed or creativity. It’s about giving teams a way to slow their thinking down just enough to decide whether a moment is building something or simply passing through.

As a final thought, a line from brand voice and copywriter Vikki Ross has been sitting with me all week. She wrote about waking up to brands jumping on another viral moment — “the latest celeb gossip that’s none of their business” — and ended simply with: stay classy.

It’s not a call for silence or seriousness, in a culture that rewards speed and spectacle, choosing not to jump on the Beckham-wagon might sometimes be the boldest move of all.